The Treachery Of Imaginary Data

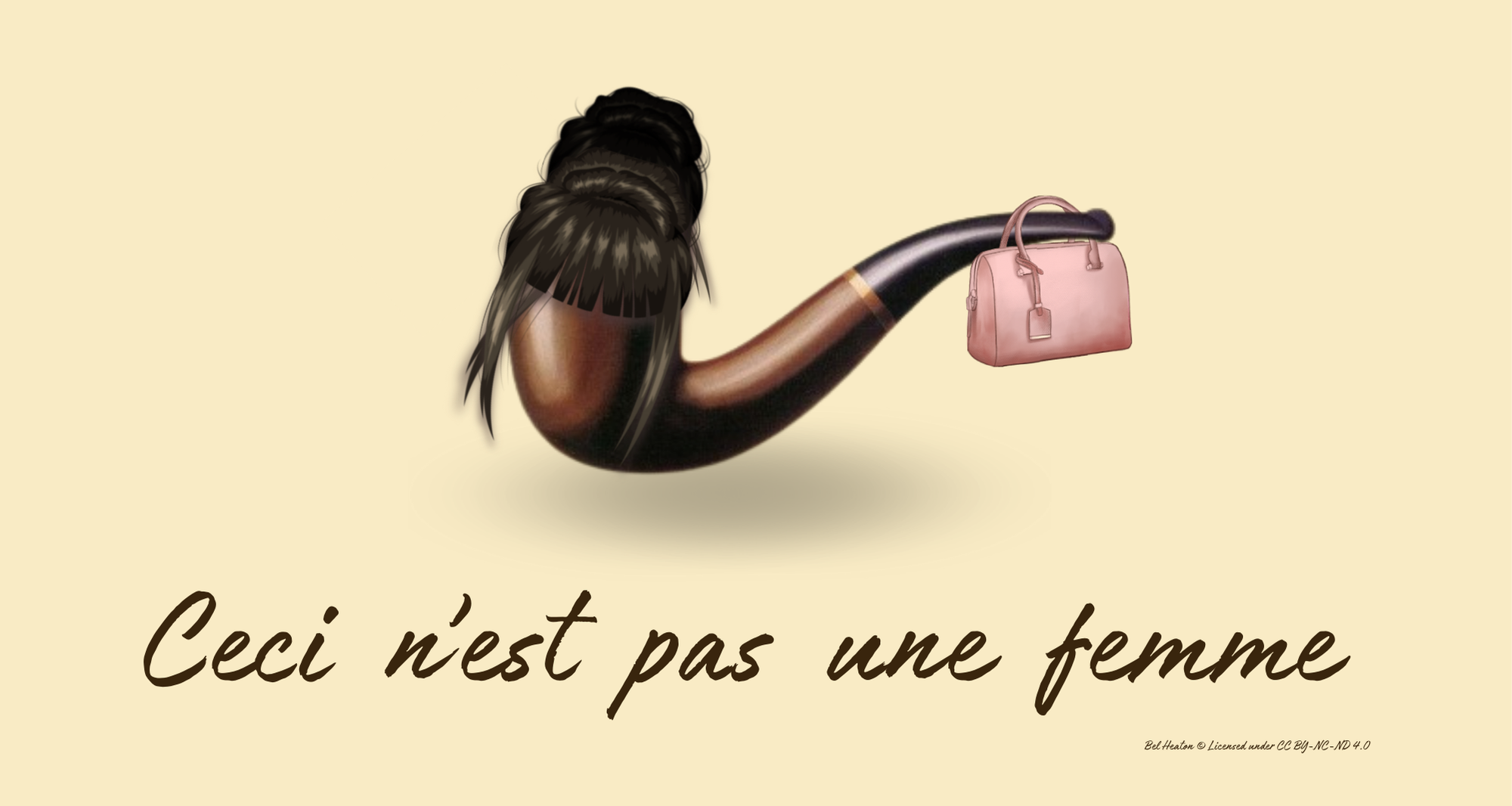

Ceci n’est pas une femme by Bel Heaton.

This article was originally published on Substack.

The object lesson of Magritte’s The Treachery of Images is that the representation of something is not the something itself.

It was while writing this article, that I was inspired to put my own spin on Magritte’s masterpiece (above). No matter the clothes, the hair, or the pronoun: a representation of a woman is not a woman.

There’s only one area that I can think of in which generalisations about women have proved to be useful - our data. Sex-based data saves women’s lives and improves our well-being. In fact, it improves everyone’s lives - on the provision that the picture it provides has material import.

This is obvious and yet, for many years now, Australian government agencies have neglected to collect accurate and comprehensive sex-based data in favour of data on 'gender’.

Case in point are recently released draft guidelines for reporting sex and gender in medical research from The National Health and Medical Research Council.

It doesn’t take a scientist to see that the draft’s vague terminology around identity markers (e.g. sex, sexual orientation, gender) is liable to confuse.

According to the guidelines, the term, 'Sexual Orientation is a ‘subjective view of oneself, that can change over time’.

Read: “Males can be recorded as women and lesbians, and vice versa.

The draft advises that researchers should record sex-based data when they deem it appropriate - essentially leaving it to researchers to make assumptions about when sex may be relevant to research before the research has been done.

The NHMRC has also provided no recommendations that address the ongoing, large scale conflation of sex-based data with gender data, something that can easily occur when different agencies share data sets between them. For example, a form with which researchers can request to use the sex-based data collected by the Australian Electoral Commission doesn’t clarify that the AEC’s voter registration forms only record gender data, not sex-based data.

These kinds of oversights present a real health and safety risk. The impact of errors, even minor ones, will accumulate every time they are shared and duplicated.

Sex-specific illnesses like prostate cancer, cervical cancer, maternity death, and Fragile X syndrome, couldn’t care less for our pronouns. Men, who experience 53% of the share of ill health and death, and poorer mental health than women also stand to lose from the the erosion of sex-based data.

In Victoria, seven male police officers have come under investigation for falsely identifying as non-binary employees (presumably in the hope of gaining a larger clothing stipend). With a few lazy strokes of a pen, a bad actor can now falsify employment records, undermine inclusion initiatives, and steal provisions set aside for women in one fell swoop.

It’s also been confirmed that gender is taking precedence over sex in crime reporting and in prisons. While the extent of the practice and its impact on Australian female prisoners is as yet unknown, similar policies adopted by prisons in the USA and UK have done immeasurable harm.

A report from the UK, How Police Forces Record Suspects’ Sex in Crime and Incident Reporting found that “many police forces were recording suspects’ legally recognised acquired gender, or self-declared gender/gender identity in lieu of sex registered at birth, including in the case of rape.”

In the US, the Californian Office of the Inspector General’s investigation into the transfer of men into women’s prisons has reported that men lie to enter female facilities and that incidents of sexual assault on female prisoners appear to be suppressed.

The muddling of sex and gender data reminds me of the philosopher Baudrillard’s ‘precession of simulacra’; a process by which he described, reality is concealed by successive representations of itself.

Eventually, representations of something (in this case, women) come to define that something, ultimately rendering the original unrecognisable and invisible.

This is the consequence of institutionalising the concept of gender - slowly, but surely, we become a fiction to ourselves.